Hello everyone! Welcome to my first blog.

Here, I will be sharing some interesting knowledge highlights that I learned while participating virtually in APrIGF 2025, along with the stories behind them. I hope you will find something valuable from what I have written.

Happy reading!

This is the schedule and the sessions I attended. Despite not being in good health, I was fortunate to be able to stay engaged in the sessions, turn on my camera, actively ask questions, and contribute my views drawn from my experience.

If you want to see the complete APrIGF 2025 schedule, you can visit this site: https://www.aprigf.asia/2025-program-schedule/

| Date | Session |

| Saturday, 11 October 2025 | 1. Capacity Building 2. Asia Pacific Youth IGF 2025 |

| Sunday, 12 October 2025 | 1. The Opening Plenary 2. Disaster, Data, and Digital Rights 3. Social AI, Youth, and Digital Vulnerability: A Call for Multistakeholder Action in The APAC |

| Tuesday, 13 October 2025 | 1. Regulating AI Beyond the Hype: Evidence, Equity, and Policy Priorities for the Asia-Pacific 2. Internet Governance: The Crossroads: Asia Pacific Priorities for WSIS+20 and Beyond 3. APrIGF Town Hall Session |

| Wednesday, 14 October 2025 | 1. APrIGF 2025 Fellowship Program: Fellow Presentation |

Capacity Building

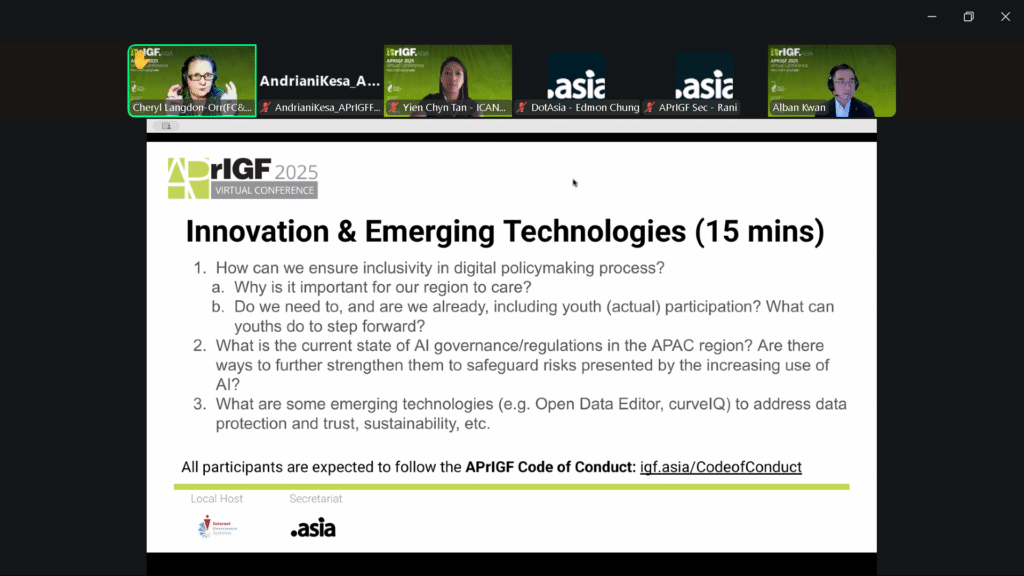

In the capacity-building session, we were given several options for breakout group discussions:

- Access & Inclusion

- Security & Trust

- Innovation & Emerging Tech

- Resilience

- Sustainability

I was assigned to the Sustainability group. Based on the work I have done with the Community Centered Connectivity Initiatives, we have five principles to keep the internet running: Low Tech, Low Maintenance, Low Learning Curve, Low Energy, and Local Support, because they still require support from multiple stakeholders.

Asia Pacific Youth IGF 2025

In the Asia Pacific Youth IGF 2025 session, I shared a story about the AI-related work that we have been doing with CCCI and our colleagues who are part of the Rembuk Nusa consortium. Before moving on to AI, we carried out a Digital Literacy Roadshow in 11 locations across 10 provinces in Indonesia, together with the Digital Access Programme of the UK Embassy. This step was taken to address the digital divide and to provide a foundation for end users before they engage in meaningful use of the internet.

After we felt that the areas we support had gained adequate internet access and basic digital literacy, we then moved further to conduct data collection using IoT and AI through the Community-based Innovation Lab for Climate Resilience (Co-LABS) — Climate AI Adoption in Indonesia’s Blue Economy with the GIZ Indonesia and National Development Planning Agency. In terms of building AI capacity for rural and remote areas, there are several challenges, such as language limitations and inadequate access. Therefore, we conducted basic training starting from AI fundamentals and examples, to how to use it, including how to create prompts. Going forward, what we aim to do is make AI usage more meaningful in order to support MSMEs in our assisted regions.

The Opening Plenary

In the opening plenary session, one thing that stood out to me was a statement by Ferdous Mottakin, Head of Government Affairs and Public Policy for South Asia at TikTok, regarding his view as platforms evolve — specifically on what policies or norms should be prioritized to ensure a safe, sustainable internet for all. According to him, there are five frameworks:

Policies are required to be in place, and they are expected to be guided by clear principles and made context-sensitive. The principle of context sensitivity has already been mentioned by TikTok in relation to these policies. Human rights — including freedom of expression and privacy — are required to be embedded and made inherent to these policies. UNESCO’s guidelines are currently being localized in Bangladesh, the Maldives, and Sri Lanka so that freedom of expression, access to information, and privacy are fully upheld, and so that all stakeholders are ensured to be involved throughout the process of developing these guidelines.

Youth engagement and the provision of digital literacy skills are required to be ensured, as young people are to be placed at the center of this endeavor. New skills are to be acquired so that the digital environment can be navigated and new information ecosystems can be effectively contributed to.

Data sovereignty and cross-border data flows are increasingly being brought into internet governance discussions. Regional work on contractual clauses for cross-border data transfers is being carried out, and national initiatives such as the development of data protection policies in Bangladesh are being explored to ensure adherence to human rights while data flows are optimized.

A multistakeholder model of governance is to be adopted so that all parties, including the private sector, are seated at the table and meaningful outcomes can be yielded.

Lastly, platform design is required to be made inclusive and human-centered so that communities with low connectivity and people with disabilities are enabled to access, use, and participate fully through these platforms.

Disaster, Data, and Digital Rights

In the Disaster, Data, and Digital Rights session, everyone was invited to share their stories. One of them, a participant from the Philippines named Aris, shared that they had experienced three consecutive earthquakes with a magnitude of 6.9 on the Richter scale down south of the Philippines. And just yesterday (11 October 2025), a volcano erupted. The data did not arrive quickly. Even though the country is often referred to as a “social media champion of the world,” it turned out that the disaster response in the city took three days.

Aris used to be part of the Red Cross volunteer team and he learned about the Incident Command System. A big part of the Incident Command System is communication. Meanwhile, the internet infrastructure at that time was completely paralyzed, and some people shared in the chat that even disaster warning information arrived 3 to 30 minutes after the disaster had already occurred.

Pavel Farhan, as the speaker, explained that we need an Early Warning System (EWS) and that the EWS and connectivity are human rights issues, not just an engineering problem.

In addition, Selu Kauvaka from Tonga Women in ICT of the Kingdom of Tonga explained that they have been conducting trainings starting from digital literacy to steps to take when early signs appear or when a disaster occurs. I also asked whether they already had materials/modules for these trainings, and it turns out they have created modules in two languages — Tongan and English — so they are ready to be distributed. I can’t wait to reach out to her through email!

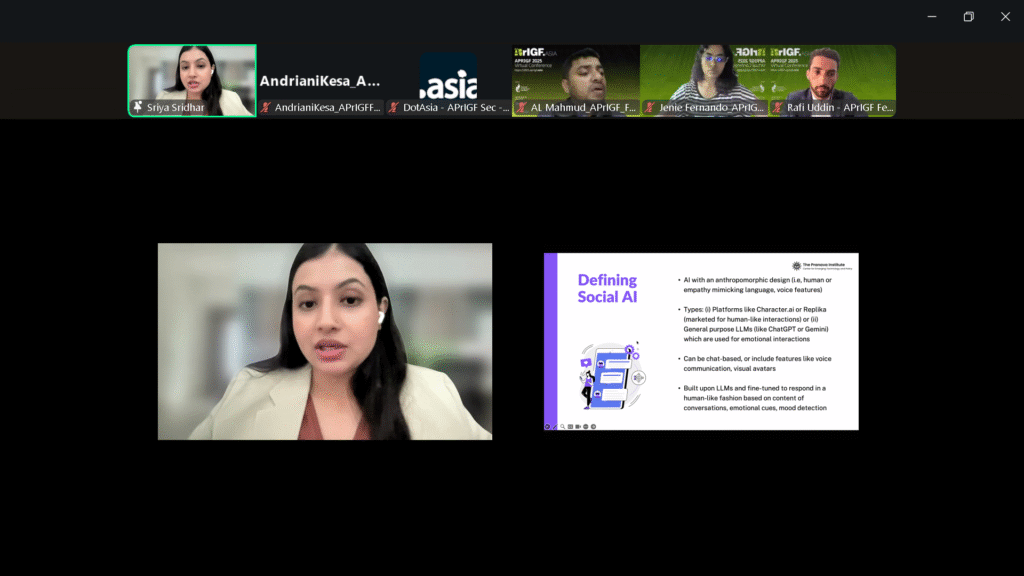

Social AI, Youth, and Digital Vulnerability: A Call for Multistakeholder Action in The APAC

Ms. Sriya Sridhar as a research fellow from The Pranava Institute, India flooring about Social AI, Youth, and Digital Vulnerability: A Call for Multistakeholder Action in The APAC

The speaker highlights the rise of AI tools built on large language models (such as ChatGPT and Character.AI) that can convincingly simulate human conversation, empathy, and emotional support. Current research shows that a dominant use of these AI systems — especially among young people — is for personal therapy, emotional companionship, and support. This trend is seen as both an opportunity and a serious risk that requires urgent attention from policymakers and regulators.

Because AI now mimics human language so well, people may anthropomorphize these systems and wrongly perceive them as sentient or emotionally understanding, which can affect how humans relate to machines. Some AI chatbots even claim to provide therapy-like support, raising concerns around mental health, safety, and manipulation.

The presentation defines “social AI” as AI designed with human-like features that can mimic empathy and adapt emotionally based on interaction content. These systems include both:

- Purpose-built emotional AI (e.g. Character.AI, Replika)

- General LLMs (e.g. ChatGPT, Gemini) that are increasingly used for emotional engagement

Their research project, “The Feeling Automata Project,” investigates the risks of such systems, how they produce emotional and manipulative responses, and why regulatory and policy frameworks are urgently needed to address these challenges.

Researchers have begun examining the rise of emotional and companion-style AI systems by conducting a literature review and multi-stakeholder consultations with psychologists, academics, lawyers, policymakers, and developers of AI and mental-health apps. Their upcoming report will explore whether such systems are socially desirable — particularly for children, teenagers, and youth — and will propose regulatory and policy responses related to age restrictions, ethical design, consumer protection, mental-health safeguards, child safety, and data privacy.

The scale of use is already significant: one emotional AI app recorded 40 million downloads in 2025, more than five known wrongful-death lawsuits have been filed involving AI chatbots (including minors), and surveys in the US and UK show that a large share of teens and children now use AI for emotional support. Loneliness also affects one in six people globally, making such tools more appealing across age groups.

Documented harms include addiction and dependency on AI companions, abusive behavior encouraged by the absence of consequences, harmful outputs generated and mirrored by AI, disruption of healthy human relationship development (especially in children), and psychological risks such as deception, misinformation, and exposure to conspiracy content.

Regulating AI Beyond the Hype: Evidence, Equity, and Policy Priorities for the Asia-Pacific

The panel emphasized that AI regulation requires a distinct approach from traditional technology regulation, as AI necessitates a balance between governance and innovation. Overly restrictive rules—such as strict privacy laws or limitations on data mining—can hinder technological development and access to datasets needed by developers. Therefore, regulation must be designed in a way that still allows innovation to move forward.

The panelists emphasized that rulemaking should not be driven solely by the government or the private sector, but must involve a range of stakeholders, including small startups, civil society organizations, and other relevant entities. In addition to formal legislation, public procurement policies can also shape responsible AI practices through sector-specific guidelines.

Sitha Laksmi provided an example from Indonesia, where the government is currently drafting an AI policy map and making it open for public comments. The document explicitly mentions the need to balance regulation and innovation, but there are various limitations in practice, such as infrastructure, capacity, language, and other issues. In response, civil society organizations in Indonesia submitted comments using a human rights framework, which is considered capable of functioning in two ways: regulating AI while still allowing innovation, and at the same time providing safeguards for vulnerable and marginalized groups.

The panel also highlighted the limited institutional capacity in developing countries, meaning AI regulation must be realistic and designed with existing constraints in mind. Overall, the discussion emphasized the importance of balance, multi-stakeholder involvement, the role of public procurement, and frameworks that enable innovation without ignoring risks and public protection.

Internet Governance: The Crossroads: Asia Pacific Priorities for WSIS+20 and Beyond

Key Priorities for WSIS+20 and Beyond

The panelists agreed on several critical priorities for the WSIS+20 review and the future of internet governance, particularly for the Asia Pacific region:

1. Preserving the Multistakeholder Model

- The Model: This was the most frequently emphasized priority. All speakers stressed the importance of maintaining the current multistakeholder model of governance (involving governments, the private sector, the technical community, civil society, and other stakeholders) as essential for an open, secure, and interoperable internet.

- Concern: The risk of centralized control or “technical fragmentation” that could arise if the model is eroded, making decision-making slower, less transparent, and excluding key internet stakeholders.

- ICANN’s Focus: To preserve the multistakeholder model and recognize the unique role of the technical community in ensuring the internet remains technically sound and interoperable.

2. Strengthening the Internet Governance Forum (IGF)

- Permanent Mandate: All speakers supported the idea of a permanent mandate for the IGF, with several noting it was a pleasant and direct surprise in the Zero Draft.

- Ecosystem: Emphasis on the IGF ecosystem, which includes the National and Regional Initiatives (NRIs) like the Australian IGF and APRIGF, as critical platforms for digital policy discussion.

- Improvement: Calls for a strengthened secretariat and sustainable funding for the IGF.

- Safeguard: A significant concern raised by Joyce was the need for safeguards to ensure that making the IGF permanent under the UN does not lead to an erosion of its fundamental multistakeholder nature and its current way of working.

3. Connectivity, Digital Inclusion, and Bridging Digital Divides

- SDGs & Norms: The Australian government noted that the WSIS vision is “essential for achieving the SDGs and setting global norms for the digital environment.”

- Policy Focus: Advancing policy issues like connectivity, closing digital divides, promoting innovation and investment, and increasing the participation of youth and underrepresented groups (including women and girls, vulnerable, and marginalized groups).

- Underrepresented Groups: Adrian (Internet Society) specifically highlighted the need to address the enabling environment for universal connectivity, particularly in relation to Small Island Developing States (SIDS), Least Developed Countries (LDCs), and Landlocked Developing Countries (LLDCs).

4. Implementation and Coordination

- WSIS Action Lines: Ensuring the continuation and enunciation of the WSIS Action Lines.

- Complementarity with GDC: Avoiding duplication between the WSIS+20 outcomes and the Global Digital Compact (GDC), and instead ensuring their complementarity with clear delineation of roles.

- Coordination: Improving coordination among stakeholder organizations across the internet and digital governance ecosystems.

Reflections on the WSIS+20 Zero Draft

The general consensus was that the Zero Draft is a good start and a strong basis for further negotiation, though it requires more detailed work.

Hits (Opportunities & Positives)

- Reaffirmation: Strong reaffirmation of the multistakeholder model and the proposal to make the IGF permanent.

- Human Rights and Inclusion: Emphasis on human rights online, digital inclusion, and the need to bridge persistent digital divides.

- Positive Elements: Inclusion of support for linguistic diversity, acknowledging the risk of fragmentation of the Internet architecture, and recognizing the evolution of the IGF as an ecosystem.

- Implementation: Section on implementation roadmaps and measurable targets for better accountability and progress tracking.

Misses (Concerns & Areas for Improvement)

- Lack of Detail: The text is high-level and lacks sufficient detail, especially regarding how certain goals (like permanent IGF and complementarity with GDC) will be implemented.

- GDC Duplication: Concern over the risk of duplication with the Global Digital Compact and the need for a clearer delineation of roles among the various UN agencies (UNDESA, ITU, UNESCO) involved.

- Localization: The draft is too general, lacking an approach that addresses the diversity of needs across different economies (developed, developing, LDCs) and regions like Asia Pacific; there is no one-size-fits-all approach.

- Inclusion Gaps: A suggestion was made that the draft, while mentioning many groups, does not reflect the needs of internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the APAC region (e.g., in countries of conflict like Palestine, Burma, or Middle Eastern countries).

Call to Action: Inclusive Participation

The panelists strongly asserted that it is not too late to participate and influence the final outcome document.

| Panelist | Call for Action | Key Message |

| Joyce | “Participation is not passive. To preserve the #MultistakeholderModel, everyone must not just speak up, but actively pitch in the effort to do the work.” | Active Participation: Don’t just sign up; actively contribute effort. |

| Adrian | “The Internet is for everyone. The future depends on all of us enacting, listening, and building together. #FutureofInternet” | Collective Building: Act together to shape the future. |

| Angela | “The multistakeholder system is available for us. To have your voice heard & ensure proper representation, speak up in an informed way via the proper channels. #WSIS20″ | Informed Advocacy: Use available resources and channels to make your voice count. |

| Veronica | “To influence the final text, speak up, participate, get involved. Collaborate with allies & speak in a harmonized voice to be more impactful. Let your Gov be your voice! #InternetGovernance” | Harmonized Voice: Collaborate with others and engage your government for greater influence. |

How to Get Involved Now

Capacity Building: Focus on capacity building for underrepresented economies, including financial support, remote participation, and technical training.

Use Regional Platforms: Host and join local conversations and dialogues to raise awareness and localize the global context.

Leverage Networks: Engage with the APRIGF working group (which has already submitted a consolidated outcome document), the informal multistakeholder sounding board (Co-Facilitators’ initiative), and organizations like ICANN (which has the WSIS Outreach Network mailing list) and the Internet Society (ISOC) (via their chapters).

Engage Government: Reach out to your respective governments, as they rely on stakeholder expertise to advocate for national priorities in the negotiation room.

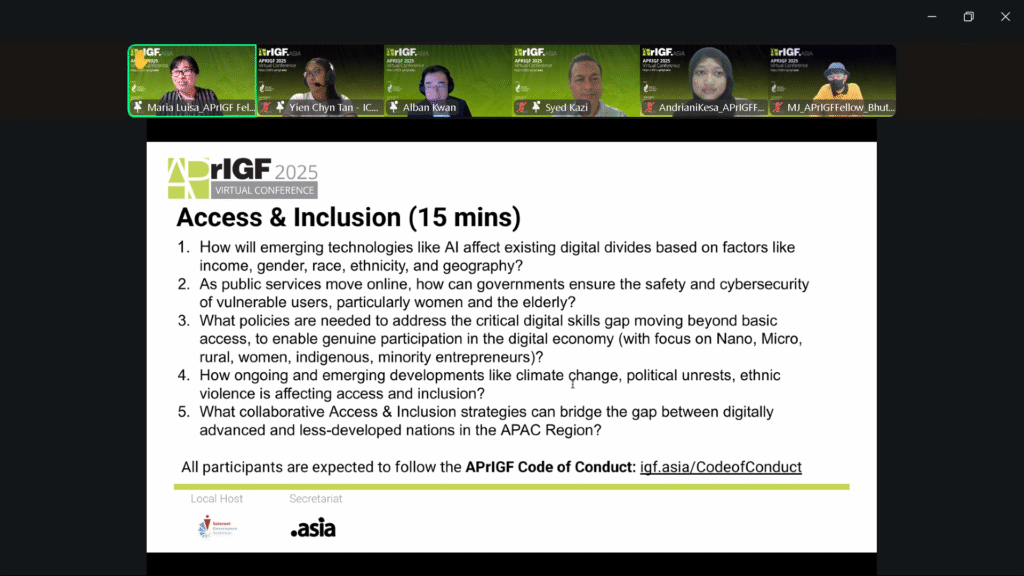

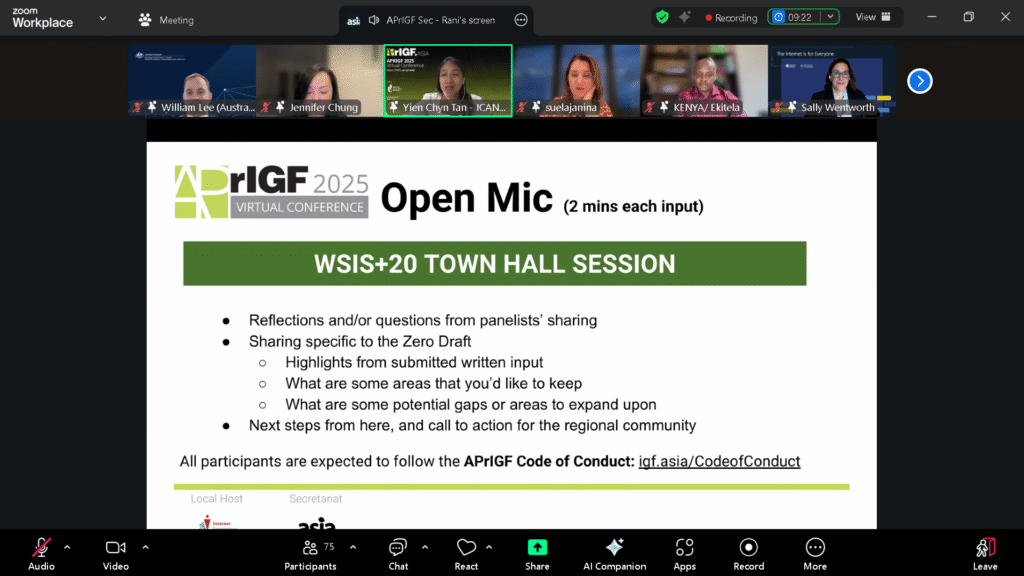

APrIGF Town Hall Session

For the Access and Inclusion theme, I answered question number 5: ‘What collaborative access and inclusion strategies can bridge the gap between digitally advanced and less developed nations in the APAC region?”

1. Regional Knowledge and Capacity Sharing

We must leverage existing regional platforms, such as the APrIGF, to establish sustained knowledge and capacity-sharing initiatives. This approach moves beyond simple information dissemination, prioritizing peer-to-peer learning platforms that allow nations to exchange practical, context-specific solutions. By formalizing these exchanges, we enable developing countries to rapidly adopt proven digital development models and build the internal expertise necessary for sustainable digital growth.

2. Multistakeholder Collaboration for Community Connectivity

Bridging the final-mile gap requires robust multistakeholder collaboration. This strategy involves actively uniting governments, the private sector, the technical community, and civil society to deploy and manage connectivity solutions directly within underserved communities. Focusing on community-led connectivity models—such as those run by local cooperatives or non-profits—ensures solutions are tailored to local needs, increase local ownership, and effectively extend infrastructure beyond commercially viable areas.

3. Inclusive Policy Innovation via Regulatory Sandboxes

To foster innovation and encourage flexible access models, the region should adopt Inclusive Policy and Regulatory Innovation, notably through the use of Regulatory Sandboxes.

A regulatory sandbox serves as a safe space for policy experimentation. This mechanism allows models like micro-ISPs (Internet Service Providers) or community networks to be tested under tailored, temporary regulatory relief. This approach achieves two critical outcomes:

- It helps harmonize the enabling environment across APAC.

- It provides smaller nations with the confidence and evidence needed to permanently adopt flexible regulatory frameworks that support access to innovation.

APrIGF 2025 Fellowship Program: Fellow Presentation

I represented Buddy Group 2 alongside Hellen (Ngoc Huyen) from Vietnam and Kaung Khant Ko from Myanmar for a presentation in the session: APrIGF 2025 Fellowship Program: Fellow Presentation. Although we did not manage to finish the presentation within the seven-minute time limit, the core message of our presentation was successfully delivered.

This was the result of our collaborative work with other group members, namely Ashutosh Maharaj from Fiji and Rafi Uddin from Pakistan. Even though our time zones were significantly different—I was working in the late afternoon while they were already approaching midnight—they were still willing to participate in the discussion. I feel my groupmates demonstrated great dedication. I also want to acknowledge Swaran Ravindra as our Mentor, who was always available to ensure we were doing well.

Summary of the Presentation: Digital Inclusion and Mitigating Connectivity Divide in APAC

I. Introduction and Problem Statement

- Digital inclusion is crucial for social and economic development in the APAC region.

- Despite wide mobile broadband coverage (96% of the APAC population is covered), meaningful internet use still lags. Only about one-third of users engage productively online for education, health, or work.

- The Connectivity Divide persists across urban-rural, income, gender, and age lines, which also exacerbates the Digital Language Divide and limits resilience against climate-induced disasters.

- Serious urban-rural and regional disparities exist in both access and quality.

II.Barriers to Connectivity

The main challenges preventing universal meaningful connectivity include:

- Infrastructure gaps in rural and remote areas.

- Affordability of internet service.

- Shortages in digital literacy and skills.

- Gender and socio-cultural factors.

- Issues with power supply and maintenance capacity are affecting network reliability.

III. Strategies to Mitigate Connectivity Divide

The group proposed strategies focusing on inclusive infrastructure:

- Implementing multi-access connectivity by combining technologies such as fiber, satellite, microwave, cellular, and Wi-Fi.

- Developing Community Networks and local governance models to enable last-mile connectivity.

- Providing Policy support for competition, investment incentives, and innovation.

- Utilizing subsidies and programs to improve affordability and digital skills training.

IV. The Role of Community Networks

The presentation highlighted Community-based Internet Infrastructure as a key solution, emphasizing that effective community networks must be:

- Low Tech, Low Energy, Low Maintenance, and have a Low Learning Curve.

- Supported by Local Support.

The Community Centered Community Initiatives (CCCI) Ciptagelar Hotspots were used as a case study, demonstrating social and environmental impact, including:

- Official recognition and protection of Indigenous rights.

- Allocation of revenue for a reforestation program that has planted approximately 45,000 trees over five years.

V. Conclusion and Call to Action

- Bridging the digital divide requires holistic, multi-stakeholder approaches.

- Investments in infrastructure must be paired with skills development and inclusive policies.

Collective action is necessary to ensure no one is left behind in APAC’s digital future.

Closing the Curtain on APrIGF: Insights and Commitment to APAC’s Digital Future

Despite having to miss the Closing Plenary Session for an urgent reason, the spirit and lessons learned from APrIGF remain deeply impressed upon me. The experience as an APrIGF Fellow was not just about attending sessions; it was an incubator of thought that significantly strengthened my understanding of the Internet Governance landscape in the Asia Pacific.

Three main points stand out as highlights from my overall participation, and these now serve as a compass for my future contributions:

1. The Multistakeholder Model is a Necessity, Not an Option

The in-depth discussions, particularly around the WSIS+20 Review, confirmed one crucial point: the stability and openness of the Internet depend on a genuine and inclusive Multistakeholder Model. The regional consensus demanding that the voices of the technical community, civil society, and the private sector be preserved equally—even within the context of UN institutions—is a victory for effective governance. The Internet is a collective asset, and its management must reflect that.

2. Digital Inclusion Starts with the Community

The Access and Inclusion session provided a practical blueprint. We didn’t just talk about fiber infrastructure, but about how Community Networks (like the Ciptagelar case study) can solve the last-mile gap in a sustainable, low-cost, and environmentally conscious way (through revenue allocation for reforestation).

The key to overcoming the digital and infrastructure divide in APAC lies in:

- Regulatory Innovation: The use of Regulatory Sandboxes that allow small models (such as micro-ISPs) to experiment without bureaucratic hurdles, thereby giving smaller nations the confidence to adopt more flexible frameworks.

- Collective Action: Infrastructure investment must always be balanced with digital literacy development and inclusive policies.

3. Dedication Trumps Time Zones

My collaboration experience in Buddy Group 2 served as tangible proof of the immense dedication and fellowship spirit within APrIGF. Working alongside colleagues from Vietnam, Myanmar, Fiji, and Pakistan—where time differences forced us to discuss late into the night—showed the profound commitment this community has to the region’s digital future.

The support from Mentors, such as Swaran Ravindra and Syed Kazi (who left an impression of being very supportive since the pre-APrIGF mentoring phase), complemented this supportive learning environment.

Translating Knowledge into Action: The Peer-to-Peer Learning Initiative

The knowledge gained from this Fellowship is immediately being put into practice. I have launched a series of online peer-to-peer learning sessions titled: “Peer to Peer learning for Local Communities in the Operation, Maintenance, and Troubleshooting of Complex Technologies, including Internet Governance and Security.”

I will be leading to sharing the module on Internet Governance and Security, leveraging the material I studied in the ISOC Online Course. This program will run from the fourth week of October through the third week of December. This effort is done in collaboration with Akhmat Safrudin, Regional Capacity Building Coordinator – Asia (Local Networks initiatives – Association for Progressive Communications), as part of the ongoing mentorship for Community Centered Connectivity Initiatives in Indonesia.

The experience as an APrIGF Fellow has successfully transformed theoretical insights into actionable commitments. I leave this session determined to use this knowledge—from advocating for the multistakeholder model to implementation of community-based connectivity solutions—to ensure that no one in the Asia Pacific is left behind in the digital future. The journey of internet governance continues, and I am ready to contribute.

Leave a Reply